Flexible Activities, Interactions, and Assignments

We’re going to cover a lot of ground at camp in this Module! Now that we have our wireframe built out in Canvas, we’ll use the Backward Design model to learn how to create assignments and activities that are aligned with our learning objectives, which will help further flesh out your course map.

We’ll share considerations for designing activities that encourage active learning, and how to balance synchronous and asynchronous interaction. We’ll also consider the Community of Inquiry element of Cognitive Presence and how it relates to the meaning-making that results from well-designed class discussion, assignments, activities, and course content.

Our learning objectives for today:

- Create assessments and activities for one of your course modules that are aligned with your learning objectives, and include a balance of synchronous and asynchronous activities

- Explain the role that active learning plays in learner engagement

- Formulate an approach for balancing synchronous and asynchronous interaction

- Describe how cognitive presence influences successful online learning and identify ways of incorporating cognitive presence into your course design

Introduction

Hi, everyone. Welcome to Module 4 for Camp Design Online.

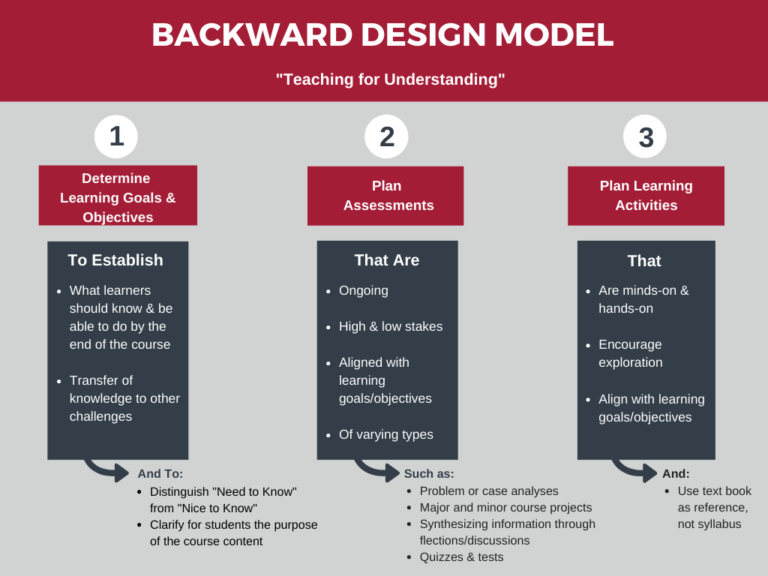

My name is Sarah Lohnes Watulak and in this video, I’m going to give a brief overview of the three main topics that you’ll be exploring in Module 4. That is steps two and three of Backward Design, active learning, and balancing synchronous and asynchronous components of your online course design.

So the first topic, backward design, which you started thinking about a couple of modules ago where you, we talked about chunking and we talked about learning objectives. So although it may seem like the next logical step after just after doing your chunking and defining your learning objectives for each chunk, would be to figure out how you’ll help students meet the objectives like designing activities. Backward design actually asks us to move from learning objectives to assessments to think about how you’ll know that students have met the learning objectives.

So assessment, and that can be in a variety of formats, including formative assessment, low stakes assessments, to check in with students to see how they’re doing, to see how their understanding is developing to what we’d call a more summative or high stakes assessment or a final assessment that is really a culmination of students’ learning and having students show what they know.

And so why would we plan for assessments before we plan for activities? Backward Design tells us that by planning for assessments, before we plan the activities, we can create learning activities that carefully and intentionally scaffold student understanding and progress toward the assessments. So that helps us avoid the scenario where we have students who say, I don’t understand what this assignment or this assessment is asking of me. I don’t understand why I’m doing this. All of our activities seemed like they were about X, this assignment is asking about Y. And so when we use the Backward Design process, it becomes clear and transparent to students in their learning how what they’re learning will be applied and applicable to to the assessment.

And so in this process of Backward Design, you’ll hear us talk about aligning learning objectives, assessments and activities. And that’s what you’ll be doing here in Module 4.

The second main topic, active learning, this section of the camp site is full of really good ideas, interesting ideas for engaging learners in online courses. And these are ideas that can be used in, no matter what modality you’re using, whether asynchronous or synchronous. And so I encourage you to look through some of these ideas around game based learning and project based learning and experiential learning that we have on the Camp Design Online materials. And perhaps they will give you some ideas for active learning activities for your classes.

The third topic, balancing asynchronous and synchronous components of your course, is related to active learning. As I hinted in the sense that when we talk about synchronous and asynchronous, what we’re talking about are the modalities in which students actively engage with each other and the course materials.

So this idea of synchronous and asynchronous online learning has been a bit of a hot button topic for professors everywhere during this remote teaching, and I’m excited for the opportunity to be able to talk through some of some of these ideas with you all during Camp Design Online.

One thing that I want to emphasize is that it’s it’s a common misperception that we hear from faculty that asynchronous means self taught, that a learner goes through the materials without interaction with their peers or with instructors. And although that is one version of asynchronous learning, if you’ve ever had to take a workplace training, for example, where you just go through a bunch of videos and an answer quiz questions, that is a version of asynchronous online learning.

However, when we talk about asynchronous online learning in Camp Design, we are talking about asynchronous learning – yes, it’s learning that happens when you’re not all in in in the room together, it’s spread out over time – but it is active. It is engaged. It does involve peers. And it does involve instructors. Designing those types of activities and designing them well does take a bit of thought and effort. And hopefully you’ll gain some ideas for that here in Camp Design Online.

Now, when you’re used to teaching synchronously in live sessions, I think the reorientation can can be challenging. And I’d suggest that one good starting places to move away from saying this is what I usually do in my live class or this is what I usually do in, in my seventy five minute class and my in my 90 minute class, to move to thinking about what types of activities and assignments and interactions you have with students to achieve your learning objectives regardless of modality.

So if we can shift our thinking toward away from, you know, this, again, this is what I usually do in my 75 minute class, to this is what I want my students to learn, it opens up possibilities for thinking about how students will learn, including through what modality. And I think that’s a great starting place for these conversations.

Finally, in considering that balance of synchronous and asynchronous, we think about how can we make sure that the synchronous sessions, if we use them, are being used not because they look most like our in-person classes, but to achieve the learning objectives that are best suited to that type of synchronous interaction.

And so we’ve suggested folks to think about the live, using the live sessions for connection and collaboration and being in community with one another. So we look forward to interacting with you around all of these ideas.

Please dive into the camp materials, go to Canvas and participate in some of the optional activities. And we look forward to talking more with you about them.

Module 4 Activities

We invite you to complete one or more of the activities below, in order to dig deeper into concepts you learned about in the module. The key assignment is designed for you to apply what you learned to the design of your own online or hybrid course.

Once you’ve completed the readings and reviewing the rubric, head over to the Canvas site, where you’ll find detailed instructions for each of the activities. If you choose to submit the key assignment, you’ll receive feedback from DLINQ camp counselors. You’ll find a button at the bottom of this page that will take you to Canvas.

Complete the readings and viewings on this page about the Backward Design model steps, Active Learning, Cognitive Presence, and balancing synchronous and asynchronous activities.

Reflect and discuss: What modalities to do you plan to use to engage students with the content and with each other?

Design a group assignment: Working together in small groups of your own choosing, select one of your courses and modules and design a group activity or assignment for that module.

KEY ASSIGNMENT: Design an active learning assignment using steps 2 & 3 of Backward Design. You can turn this in for feedback from DLINQ Camp Counselors.

The Backward Design Model

Steps 2 & 3: Mapping Assessments and Activities

On Day 2 of camp, you were introduced to the Backward Design model, a course design approach that is framed 3 questions:

- What’s our destination?

- How will we know we’re on the right road?

- How will we get ourselves there?

You’ve answered the first question, by identifying the modules of your course and the learning objectives for each module. Today, we’re going to answer questions 2 and 3 by identifying assessments and activities that align with your learning objectives.

Although it may seem like the logical next step after defining learning objectives is to figure out how you’ll help students meet the objectives, Backward Design asks us to move from learning objectives to assessments. How will you know that students have met the learning objectives? Assessment helps learners know whether they are on the right road and whether our instruction is leading them there.

Why plan for assessments before activities? By planning for assessments before we plan the learning activities, we can create learning activities that carefully and intentionally scaffold student understanding and progress toward the assessments.

For example, if your summative (final, graded) assessment for the course is to have students create a podcast series on the impact of COVID-19 on social structures, you’ll want to have students build up to that throughout the semester. As they learn relevant content, they might engage in activities such as identifying podcast topics, creating scripts, learning to use podcasting software, and collecting resources — and, have a chance to share and get feedback on all of these pieces.

And a reminder, as you consider what assessments align with your learning objectives for a module and/or a course: assessments are not the same as grades. Assessments can be ungraded opportunities for students to review their learning progress, receive input/feedback from faculty, and adjust/re-evaluate their path. Plan to include both formative (low-stakes, feedback) and summative (higher-stakes, graded) assessments. (The podcasting project example above could include formative assessments at all of the stages leading up to the final, completed podcast, which represents the summative assessment for the course.)

Dig Deeper

- Understanding by Design – from Vanderbilt Center for Teaching and Learning

- Summative and Formative Assessment – Indiana University Center for Innovative Teaching and Learning

- Transparent Assignment Design – TILT Higher Ed project

- ACE framework from Plymouth State – suggestions for creating assignment-level and course-level elements that are adaptable, connected, and equitable

- Research Assignments for Remote Courses – Guide created by Middlebury librarians for research-based assignments that allow students in remote courses to practice core information literacy skills

Active Learning

Active learning, or “learning by doing,” involves learners in action-oriented experiences to help them deeply engage with course content. The goal of this style of learning is to get students to engage, rather than passively take-in. In an active learning environment, students interact with the course material through reading, writing, researching, talking, problem-solving, synthetical thinking, constructing, deconstructing, and reflecting. Ideally, rather than completing these activities in isolation, learners are given opportunities to work collaboratively and receive feedback from one another as well as the instructor.

The dynamic that occurs through shared, constructive feedback and collaboration helps to form a learning environment rooted in connection and community, the importance of which is discussed specifically in the module on “Social Presence.” We introduce the principles of connection and community here to emphasize that learning is, fundamentally, a social process and that active learning can be a powerful (but not exclusive) vehicle to facilitate it.

Some may worry that active learning means a complete abandonment of content-driven lectures, however this is far from the truth. Rather, it presents instructors with opportunities to imagine activities that will help learners develop a deeper and more authentic understanding of the lecture content that is shared and shaped with feedback.

In most cases, planning traditional learning strategies that are more passive in nature takes less time than planning and assessing active learning assignments for an entire semester or summer session. While some passive learning strategies in a course may be indicated (we are not suggesting that all passive learning is ineffective or unnecessary), it is also important that planned activities align with passive learning experiences.

Dig Deeper

Experiential Learning

- Experiential Learning at Middlebury

- What is experiential learning and how can I implement it? (Faculty Innovation Center, University of Texas at Austin)

Project-Based Learning

- Buck Institute for Education PBL Works (great resource for all things project-based learning)

- Free online platforms that support PBL

- ArcGIS (story mapping works especially well as a PBL assignment, Middlebury ITS-supported)

- Raptor Lab (science-inquiry, UMN)

- WeExplore (multimedia storytelling, UMN)

Game-Based Learning

- Why Games? (University of Toronto Libraries)

- Pedagogy of Game Based Learning (University of Toronto Libraries)

- Game Based Learning Best Practices (University of Toronto Libraries)

Research-Based Learning

- Research Assignments for Remote Courses (Middlebury College Libraries)

Additional Resources

- Making Online Learning Active – article with a large list of tools that support active learning (concept mapping, data viz, timelines, collaboration, portfolios, and more)

- Active Learning for your Online Course: 5 Strategies Using Zoom

Balancing Synchronous and Asynchronous Activities

Asynchronous interactions allow students to join and participate in class activities on their own schedule (though usually by a deadline). An example of asynchronous learning is a pre-recorded lecture that students watch followed by discussion board interactions. Some asynchronous learning is self-paced – meaning, no peer or instructor interaction – which you may have experienced if you’ve ever had to complete a workplace training module. However, we want to stress that asynchronous learning can also be active and completed in a learning community of peers and instructors, and when we say asynchronous online learning, we are talking about the latter – online learning that is designed for peer and instructor interaction, but which takes place over time, instead of at the same time.

Synchronous interactions require students to join and participate in class activities “in real time,” all at the same time, just as if they were sitting in your classroom. An example of synchronous online learning is a live Zoom session where students and faculty are logging into a Zoom room at the same time for a discussion.

Synchronous learning provides an opportunity to see and hear and interact with each other in real time. We know from student feedback on the spring semester that for some students, Zoom meetings became an important connection point. That is significant. At the same time, some students could not participate in the live sessions, for reasons of bandwidth or access to equipment or life circumstances tied to living and learning in a pandemic. Even when professors provided alternate content, such as a recorded Zoom sessions, these students did not have the opportunity to interact with peers and professors around the learning materials – they became flies on the wall, rather than full and equal participants in the learning experience.

So, where to from here? Jennifer Casa-Todd suggests a reframing away from debating asynchronous vs. synchronous; instead,

“we should be asking ourselves how can we help [our students] feel connected and supported; in their learning and with their well being.

We should be asking, is it more effective to have my students watch a video I created to learn a concept and then meet in real time to go over any issues or is it more effective to teach an interactive lesson in real time?…

What are some of the tools which will allow my quiet students to be engaged?

How can I ensure that the students who do have the ability to and do attend synchronous sessions feel that it has been a good use of their time?”

We would add another question to this list: What is it that you hope students will know or be able to do by the end of the activity? It helps to be very specific – “discuss” is not a specific learning objective. What do you hope students will achieve during a discussion? Analyze, compare and contrast, solve a problem? – these all represent more specific outcomes.

Once we’ve identified the learning objectives, we can identify ways of achieving the objective. There are many ways of engaging students in activities that ask them to work together to analyze, compare and contrast, or solve a problem. Some of these may be synchronous, some asynchronous – and some may intersect the two. Jesse Stommel shared two interesting examples along these lines:

- “Students could brainstorm key questions asynchronously online, discuss those questions synchronously face-to-face, and then students who couldn’t be present in the moment could write or record their own responses, which then seed future online and face-to-face discussions.”

- “A short provocation, a mini-lecture (both recorded and presented live), could jump start discussion in small groups with some of those small groups working synchronously in a classroom and some working asynchronously online.”

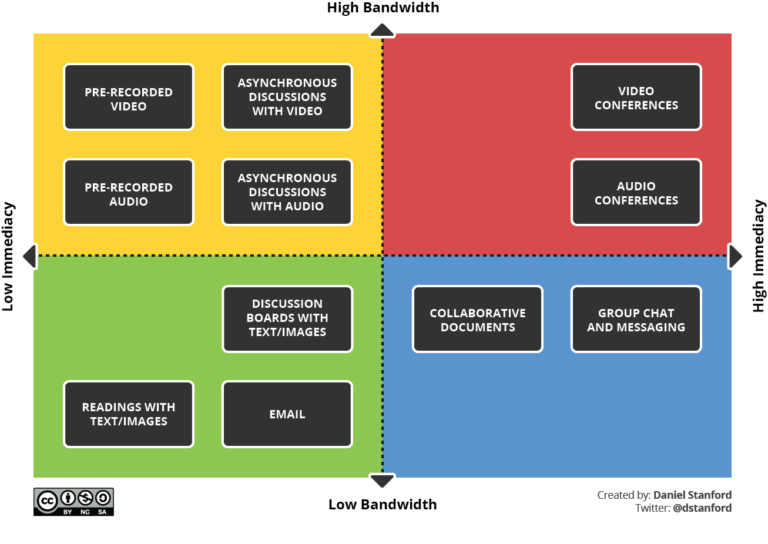

Daniel Stanford of DePaul University approached the question from a different perspective, by classifying activities on a Bandwidth Immediacy Matrix, rather than as synchronous and asynchronous. Using immediacy and bandwidth as the axes highlights the tension between the two, and illustrations ways of providing a range of options for your students.

Given the concern that using synchronous learning as the primary means of delivering course content will not, in many cases, result in an equitable learning experience for all students, we encourage you to use these questions and frameworks to develop an approach that blends synchronous and asynchronous in ways that provide the opportunity for all students to fully participate in your course. We’d like to think about synchronous and asynchronous as working together, rather than at opposite and opposing ends of a spectrum. Research indicates that blending synchronous and asynchronous interactions in remote/online courses can promote social presence and combat students’ feelings of disconnectedness while supporting student learning.

How can we blend asynchronous and synchronous learning to best support student learning? How can make sure that the synchronous sessions are being used not because they look most like our in-person classes, but to achieve the teaching/learning goals that are best suited to that kind of synchronous interaction?

Perhaps most importantly, how can we ensure that all of our students feel supported and can make meaningful use of the synchronous and asynchronous portions of our courses?

Dig Deeper

- Videoconferencing alternatives: How low-bandwidth teaching will save us all – Daniel Stanford’s blog post explaining the matrix

- 8 Ways to be More Inclusive in Your Zoom Teaching – Kelly Hogan and Viji Sathy in the Chronicle

- Synchronous vs. Asynchronous Learning – Jennifer Casa-Todd

- Adding Nuance to the Asynchronous/Synchronous Conversation – Amy Collier

Designing for Cognitive Presence

| Design Elements | Activities |

|---|---|

| Challenge or question |

|

| Exploration of problem |

|

| Proposing solutions |

|

| Resolution |

|